Jenni Fagan’s debut The Panopticon is narrated by Anais, a teenage Scottish girl brought up in care. In the first scene Anais is in the back of a police car. Soon you find out she’s suspected of putting a policewoman in a coma. You don’t know if she did it or not, and you read on at first because you have to find out. Pretty soon you realise she’s not going to give you a straight answer, and you don’t need one anyway: Anais’s voice has grabbed you and won’t let you go.

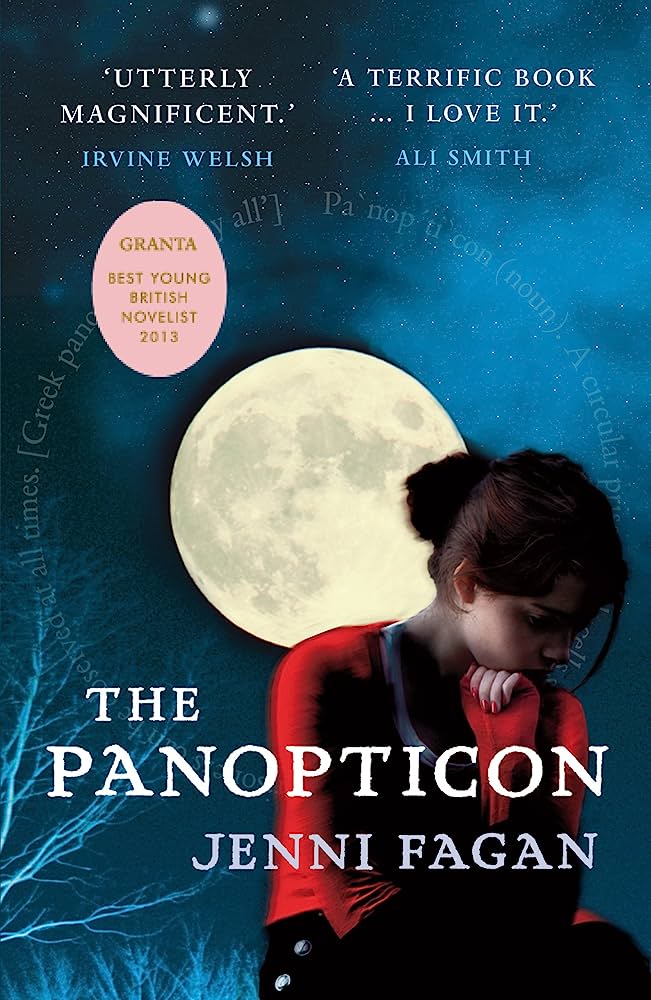

There’s an Irvine Welsh quote on the back cover that struck me as capturing this perfectly. ‘Every page sparkles with the sinister magic of great storytelling’. I held this phrase in my head when I was writing The Hotel Hokusai, trying to get some of that sinister magic down on my pages.

What I think Welsh is getting at is the ability of a novel to drag the reader in, to the point where its story and characters seems more real than the real world around you. For me, a vital ingredient to this is the sense that the novel you’re reading is saying something about the real world that no report or scholarly history could. In the case of The Panopticon, Fagan is talking (in a funny, poetic, urgent way) about what it’s like to grow up in care in modern Scotland, with your every move subject to scrutiny by a bureaucratic system. Anais is convinced this system is even trying to control her thoughts. She has to escape it, and this drive to escape is the real engine which propels the novel forwards with all the energy of teenage dreams and justified anger.

My novel has more of a traditional crime narrative engine, but I think Han, my Korean teenage protagonist, would recognise parts of himself in Anais, even though she lives in central Scotland in the 2000s, and he’s a migrant worker in 1890s Yokohama. Both are forced to grow up fast after being severely let down by certain adults supposed to be taking care of them. Both find that some adults do want to help them, but may not always know how to. And both find the unmasking of a malevolent force becomes a way to understand and negotiate their path into the adult world.

I hope I’ve managed to find a fraction of that sinister magic which Fagan’s debut is so liberally dusted with.