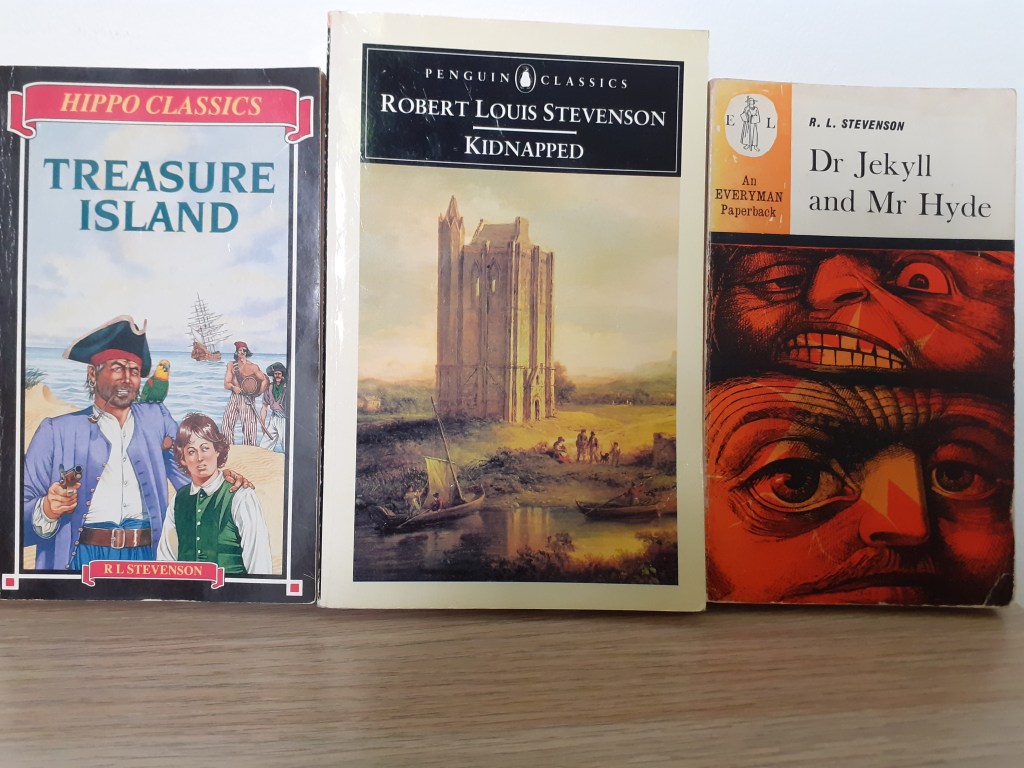

Han, The Hotel Hokusai‘s young Korean protagonist, learned his English from reading Stevenson’s Treasure Island, given to him by a dubious Scots missionary who became his adopted father before cutting him loose. My Dad gave me Treasure Island when I was about nine I think, and I lapped it up. The scene where Jim is hiding in the ship’s apple barrel, overhearing Long John Silver reveal his mutinous plans, still sticks in my mind. Classic Boys Own Adventure stuff! And yes, of course, it’s a children’s story – with a saccharine ending where Jim gets back home with the treasure and his subconscious colonial certainties still intact (unlike, say, the protagonist of RLS’s Oolala after his encounter with a family of decaying aristocratic Spanish vampiresses).

So we can’t take it seriously as an adult work of fiction…or can we? Because that’s the thing with Stevenson: he blurs those boundaries. What about Kidnapped? Davie Balfour’s journey is more obviously a coming-of-age narrative, involving a daring trek across the Highlands in the company of the glamorous Jacobite, Alan Breck. The National Theatre of Scotland have recently revamped Kidnapped into a musical stage version that turns the Balfour/Breck relationship into something a bit more bromantic than RLS might have intended. In my novel, Han and a character called Archie Nith have a relationship a bit like theirs, if Balfour was a Korean migrant to 1890s Yokohama, and Breck a socialist painter rather than an action hero. But the central theme is the same: the influence of an older man on a boy on the cusp of adulthood.

Still, if I had to pick one RLS novel that influenced The Hotel Hokusai, I’d go for Doctor Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Why? Partly because it’s his work of genius, his guarantee of immortality in just about every part of the globe. The phrase ‘Je-ki-ru-to-hai-do’ is even used in Japanese to describe someone with two sides to their personality, a ‘good’ one and a ‘bad’. But it’s the underlying notion that what we see is untrustworthy, that beneath a benign surface there might lurk something messy and sinister, which I wanted to explore more deeply, even in the context of the images we create and consume, often in the service of capital. In my novel, three Scottish artists are sent to Japan to paint a surface image of the country – what their dealer describes as ‘simplicity, innocence and restraint’ – which was in vogue in the salons of fin-de-siecle Europe. This is based on historical fact: In 1893 the Glasgow artists George Henry and Edward Atkinson Hornel were funded on a year long Japanese sojourn. Henry and Hornel feature in my novel, but I added the fictional figue of a third painter, Nith, who can’t stop scratching beneath the surface to find out what is really happening in the hybrid port settlement of Yokohama. The consequences are, of course, dangerous. Stop Press: THIS IS A CRIME NOVEL!

Or is it? Just like Jekyll and Hyde and the other Stevenson classics, I hope it blurs the boundaries of such singular definitions.