My novel The Hotel Hokusai is due to be published later this year by Glasgow’s Ringwood Publishing. This is how I came to write about a Scottish artist and a Korean migrant eel vendor in 1890s Yokohama…

In the summer of 2014, a couple of months before Scotland’s independence referendum, I was walking down Leith Walk in Edinburgh when someone handed me a Vote Yes postcard. On it was a print of a young woman emerging from a Saltire, her long red locks tumbling out from under a tam o’ shanter bunnet, her eyes saying: don’t mess with me pal. She looked as if she might have been modelled on a barmaid with a good line in put downs, except instead of a pint of Caley ’80 she was offering up a thistle.

My reaction to the image was complicated. The SNP was making the case for independence in rational terms: we have the resources, the skilled workforce and the political infrastructure to go it alone. We are inherently more socialist than England, so why do we want to be tied down by conservative governments we didn’t vote for? These arguments were good enough for me. I was more wary of the emotional undercurrents bubbling under the surface. The postcard seemed to be about those. But as a piece of art, a Celtic aesthetic statement, it beguiled me. A couple of months later the Yes dream died in the dismal drizzle of a September morning. The year after that I moved to Japan with my wife, who is Japanese, and our then one year old daughter.

*

Nagasaki, Japan, 21st April 1893.

Two men, the one in front younger and solidly built, the man behind taller, slimmer, already losing his hair, descend the gangway of a steamer onto the bustling pier. Their luggage is being carried off by Korean migrant porters: two large chests containing easels, canvases, brushes, pallete knives, oil paints and notepads.

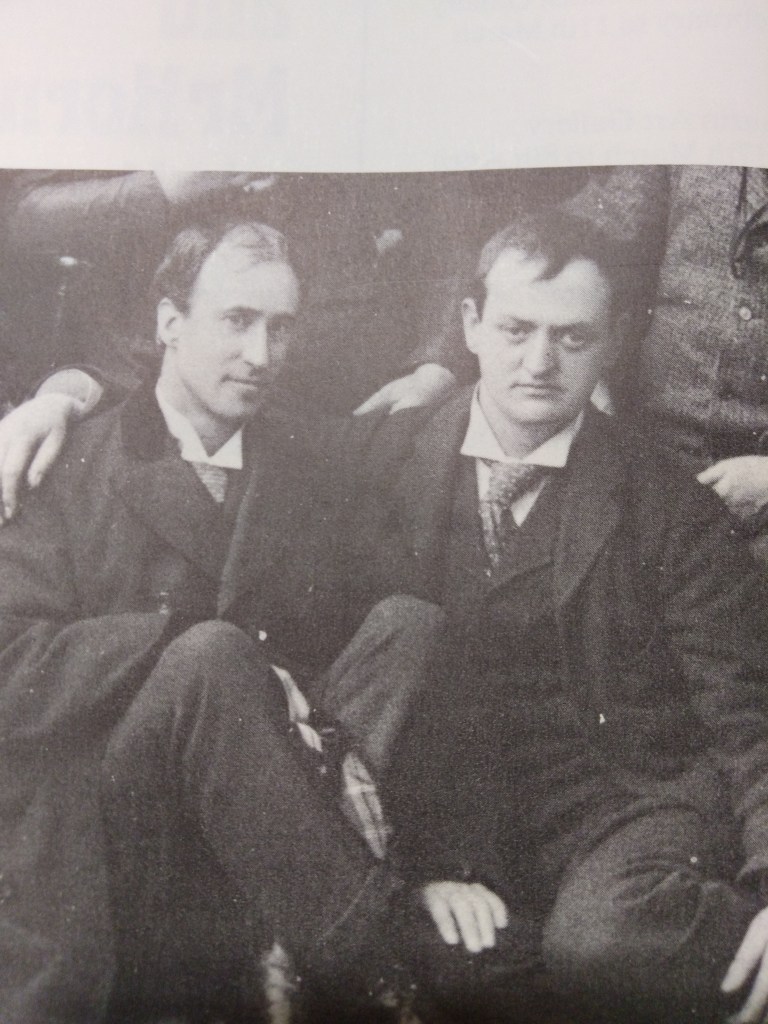

The pair are Edward Atkinson Hornel and George Henry, members of the loose collective of artists that will be known to future generations as The Glasgow Boys. They watch as their chests are loaded onto the back of a cart, anxious not to let them out of their sight – but the Scotsman who has met them off the boat assures them them the chests will be delivered in perfect condition to their lodgings. Which is where he will take them himself now… he thought they might prefer to go on foot, thus having the chance to savour at greater length their first taste of Japanese soil.

Hornel, the younger of the two artists, agrees. Henry is too busy gazing down the length of the pier, searching out the Japanese wooden houses clustered on the slope behind the waterfront warehouses. “So this is it,” he murmurs.

For both artists, the trip is the culmination of a long fascination with Japan. It has finally been made possible by the sponsorship of their Glasgwegian dealer, Alexander Reid. After a brief stay in Nagasaki, Hornel and Henry travel to the treaty port of Yokohama. They spend most of the next year there, painting furiously to satisfy Reid’s demands, before setting sail back to Scotland in the spring of 1894. On the return voyage Henry will suffer a dreadful misfortune. Most of the oil canvases he produces in Japan will be ruined by cracking and waterlogging: “I am undone,” he writes to Hornel, who disembarked separately and was more fortunate.

But all that, and its consequences for their friendship, are in the future. Now the pair are taking their first steps into the land whose artistic style they have dreamed of for so long, knowing their artistic reputations, and fortunes, are waiting to be made.

Yokohama, February 2017

“I’m interested in foreign artists who stayed here in the Meiji period,” I delivered my carefully prepared Japanese sentence.

The woman behind the desk in the basement reading room at the Yokohama Archives of History smiled politely at me.

“Do you know the name of the book you need?”

I had lived in Japan for a year and a half but I was still mightily relieved when someone replied to me in English.

“No. I’m just looking for some general background.”

“Let me see if I can help you,” she led me over towards some shelves.

A few weeks had passed since I was flicking through the web on a crowded commuter train on the Yokohama subway line and happened on a site that mentioned George Henry and Edward Atkinson Hornel. As a Scot trying to adapt to the wildly different environment of Japan, I was fascinated by how this pair, at a similar age to me, might have spent their time here a hundred and twenty years earlier. More than that: like a lot of other foreigners in Japan, I was in search of ideas for fiction. A tale of two artists in the wild Port of Yokohama, crossing paths with a young Jack London – who wrote of his escapades after a night out in the sailors’ bars of ‘Bloodtown’ – struck me as promising source material.

“This book is by a foreign artist who lived in Yokohama. Maybe it’s useful to you.”

“Arigatou gozaimasu,” I used the polite form of ‘thank you’.

“And this is the catalogue of our collection. You can come to the desk if you want to request anything.”

“Arigatou gozaimashita.” (maximum politeness)

A final smile and then she left me to pull up a chair at the table.

Two hours later I left, defeated in my quest for any information specific to Henry and Hornel. All I had was a notebook filled with scraps from Japan Mails of 1893. In the week of the 6th May there was an accident involving a cart that overturned on Jizozaka street, caused by “a pony frightened by an itinerant vendor of cakes dressed in a top hat with a drum and tin trumpet.” An image to savour, but it hardly brought me closer to knowing how my two artists had lived and spent their time in Japan.

*

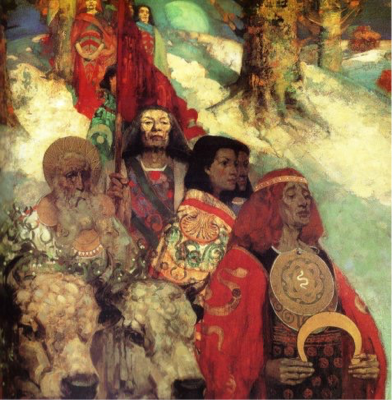

In 1890 Henry and Hornel had collaborated on ‘The Druids Bringing in the Mistletoe’. This painting, writes John Morrison, one of the leading contemporary Scottish art historians (and no stranger to a good indepedence art debate as this article plus comments shows) put them firmly at the forefront of the Celtic Revival in Scotland. The Revival was all about rediscovering a national identity independent of England, no easy task considering Scots had spend the last fifty years joining in the colonisation of half the world. To deal with this, Hornel and Henry delved back into the ancient past, something Hornel had been doing for years with his interest in the ancient standings stones of Galloway. Indeed, it seems to have been the younger artist who was the more influential, drawing Henry away from French-influenced landscapes towards these mystic themes and a more radical use of colour.

But even if it had a political motive, the commercial possibilities of Celtic Revival art were limited. Tastes were moving in a different direction. In 1757 Edmund Burke published A philosophical enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas on the sublime and the beautiful. These two concepts had been around for centuries, but Burke was the first to say they were mutually exclusive. He identified beauty with ‘smoothness’, ‘delicacy’, ‘balance’ and ‘colour’; the sublime with ‘vastness’, and ‘terror’. Burke’s delineation was immediately disputed, but it took Immanuel Kant to refine the debate in a startling way. In 1790’s Critique of Judgement, the German said that both were subjective feelings, but while the appreciation of beauty was intentionally created, the sublime was an aesthetic effect produced by something suggesting indifference to any reaction. A stormy ocean, for example. Or those druids.

By 1890, a Celtric Revivalist artwork so conspicuously sublime; so full of vastness, terror, and indifference, as ‘The Druids Bringing in the Mistletoe’, was an anachronism. The sublime aesthetic was on the way out, arguably because nature itself – the most indifferent beast of all – was being tamed. Telegraph cables had been sunk to the ocean beds, linking Britain first to America, then East to its empire as far as New Zealand. Art was moving again in the direction of beauty, and following the path of the cables, the new taste was for that version of it found in the extreme Orient. Henry and Hornel were sent by Reid to Japan in 1893 to find beauty. Find that, and they would make money as well.

*

If there is one thing that Hornel seemed to take from Japan it was an equation of beauty with the feminine. It wasn’t only that while he was there most of his paintings were of young Japanese women and girls in traditional costume, with fans poised at just the right angle. Even after he returned home he kept painting these girls. Except now he had Scottish ones to pose in their place, using photographs he’d obtained in Japan to make sure the positions and angles were the same. From 1901 he painted them in the grand old house he bought in his hometown of Kirkudbright, thanks to the money he’d made from the sale of his Japan work.

The auction had been a staggering success, Reid’s instinct for the public craving for Japonisme proving right. How George Henry must have rued the misfortune of the sticky paint. While Hornel was set for the rest of his life, the older Henry, no doubt thinking in financial terms, moved down to London where he spent the rest of his career painting society portraits. The trip to Japan caused a rift between the two formerly inseparable friends in other, more mysterious ways: at one point Hornel was contracted to give a lecture on his year in the Far East, only to pull out at the last minute. The pair had made an agreement not to talk publicly about their Japanese experiences. What was it exactly, that they didn’t want to talk about?

I was only finding this out after I had returned to Scotland myself, in 2018. Having found work teaching English to Glasgow University’s latest lucrative cohort of overseas, mainly Chinese Masters students, I was able to use my staff card and delve through material in the university library archives. By this stage I had already begun a scrappy first draft of what would become The Hotel Hokusai. my research seemed to confirm that I was on the right track: there was an aspect to this forgotten part of history that people wanted to keep hidden. As anyone who’s worked in journalism knows, a story worth telling is a story that someone, somewhere, doesn’t want you to tell. And as a fiction writer, not a journalist, I could let my imagination fill in the gaps, like the ones in Henry’s paintings where the canvases had stuck so ruinously together.